Method Notes No. 5: Sand in the Gears - or when styles change before you do.

For about eight years I've been photographing portraits – primarily of young people, often women. The images are intense, atmospheric, and emotional. They are created in spaces that are more than just backdrops. It's not just about light or the background – it's about an emotionally charged atmosphere. A conversation, a connection, a moment of openness. Only then does this special mood emerge. This atmosphere isn't just part of the image – it is the image. And it leaves a distinctive mark that probably best describes what one might call my style.

In my development, I've drawn inspiration from many photographers. Peter Lindbergh, Vincent Peters – because I find their styles powerful, minimalist, and uncompromising. But the work of earlier generations has also influenced me: Bert Stern's final photographs of Marilyn Monroe – their raw intimacy, their contrast between tenderness and directness. Eve Arnold with her quiet observation of how she accompanied people rather than directing them. Or Dennis Stock, whose series of James Dean in the rain still represents an entire era for me. These nuances, the almost intimate within the documentary, are sources of inspiration that subtly permeate my work.

These influences served as a compass for me for a long time. They were points of reference, in short. But in recent years, I've felt that they not only give me direction but sometimes also feel like too restrictive a framework. They set standards against which one unconsciously measures oneself, partly because they simply describe a long-gone era.

What concerns me are the small points of friction. Not the big break, but the many small impulses that make me realize: something needs to shift. There's a grinding noise. In some images. In certain processes. In the way I put together a setting. It's like sand in the gears – not a defect, but a grinding noise that I couldn't ignore and that, it seems, only I could perceive.

This friction was the starting point for a movement within me that began about two years ago and has intensified since last year. I started to look more closely at my work and its supporting elements, and to consider: What am I carrying forward? What remains? What is holding me back? What was I perhaps not even aware of?

Sometimes a fresh perspective is all it takes. Or an unfamiliar model. Or abandoning a familiar routine. What struck me was that it's not the big stylistic decisions that bring about change – but rather the many small decisions that lie below the threshold of perception.

In my current lecture, "More," I address precisely this topic, among others. I explore what an image truly conveys—and what we often overlook because we focus too much on the obvious, the superficial. Participants sometimes tell me they've "seen" a subject before, but then, upon closer inspection, discover aspects they had missed. Perhaps this is because we consume visual stimuli so quickly today. We scroll, we swipe, we like—but we no longer truly observe. Depth demands time. And attention. And we often compare our perceptions to what we've acquired as our "standard" over time.

I want my pictures not only to look good, but also to evoke something. Something that lingers long after the screen has been switched off.

I recently discussed these very topics on Timo Barwitzki and Stefan Magh's podcast – change, visual language, and timelessness. I used a comparison from the world of cars (guys, you know ;-)): the Mercedes E-Class of the 80s and 90s – the W124, with its clean lines, visually serene, and an almost inexplicable sense of permanence. Today, little of that clarity remains: softened lines, overloaded digital features instead of distinctive form. The confident composure has given way to the urge to please.

Or take Jaguar: a brand that once stood for elegance, understatement, and classic design – and which has become alienated from itself in recent years. An abrupt break with tradition that left many enthusiasts feeling rather bewildered. The resulting design appears techno-like, characterless, almost generic. Where there was once individuality, there is now interchangeability.

And then there are brands like Land Rover that have successfully made the transition: preserving the spirit of the original while bringing it into the present with technology and a keen sense of design. In the camera industry, it's the company from Wetzlar that has combined this clear recognizability for decades with today's technology, seamlessly blending user experience with modern technology. And that's precisely what I strive for in my photography – no regression, no stagnation, but rather a continuous evolution rooted in the present.

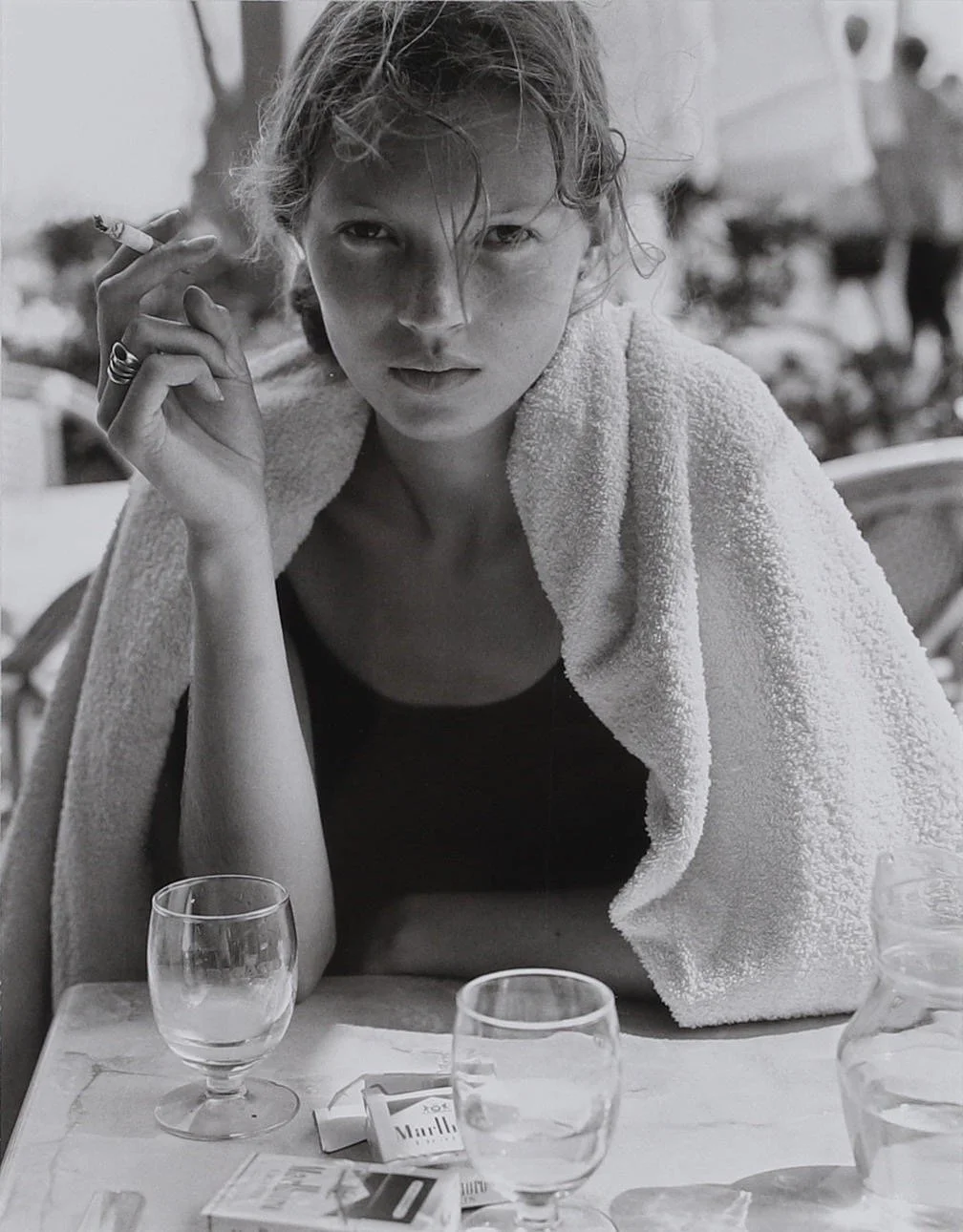

I observe the work of young photographers who look at people and contexts with a fresh perspective. André Josselin, for example, dissolves the portrait into a larger scene—for him, the image is not just the face, but the place, the surroundings, the light, the moment. Sometimes analog, sometimes digital, often raw, often poetic. Or Purienne, who, with seemingly the simplest means—a camera, natural light—captures an entire feeling of life that cannot be staged, but only felt. Or Mario Sorrenti, no longer quite so young, who decades ago preserved an entire feeling of life with his "Kate" —with a protagonist (a young Kate Moss), a holiday apartment, a summer. No styling, no concept—just intimacy, time, light.

Mario Sorrenti - KATE

All these works inspire me. Not to copy, but to engage with them. They show me: A face isn't enough. You need the scene. The space. The story behind it. And perhaps also the courage to show less of a person – but to tell more.

What carries me through this process is not a fixed concept or a specific theory. It's a more attentive observation. An openness to what changes in one's own work – and to what one may have long overlooked. It's the willingness to question oneself. And the patience to pay attention to subtle signals instead of chasing quick fixes.

Because change doesn't always begin with a loud bang. It announces itself quietly. With a small, often long-undetected crack in the familiar. With a creaking or grinding sound. With a grain of sand in the gears. Perhaps you don't even notice it at first – until a detail suddenly bothers you, an image no longer works, a moment no longer has the same power as before.

If you pause, look closely, and are willing to listen to yourself, something new can emerge from this stimulus. Not a revolution, but a gradual shift. A new precision. A different way of seeing—and showing—things.

This kind of change doesn't just affect portrait photography. It affects every form of artistic work, whether photographing people or landscapes, whether doing reportage or capturing urban spaces. When the world changes—socially, politically, climatically, culturally—our perspective changes too. And the way we capture that perspective must change as well. Otherwise, we create images that miss the mark.

In photography, this doesn't mean reinventing the wheel. It doesn't mean denying your own style or devaluing the old. But it does mean remaining open. To new influences. To different ways of telling stories. To images that might not work immediately, but ultimately say more.

I don't see this process as a break, but rather as development. As working on something that is still emerging. It sometimes feels like sorting through an overcrowded room. What stays? What can go? What have I overlooked for too long? What deserves more space? With a view far into the future.

And then the real step begins: not just perceiving what is changing – but also having the courage to move forward with it. With new ideas, with different thoughts, with a new focal length, or with completely different equipment.

Perhaps that's precisely where the real art lies: not simply trying to take good pictures, but pictures that change with you and don't just grow along with you.