Compendium Nº 1: The Last Sitting by Bert Stern

Books are much more than just inspiration to me. They're fundamental to how I think about photography. They show me how to work with people, how to capture atmospheres, how to tell stories. I simply need to have them in front of me, to be able to leaf through them and look at them for a long time. I mention them regularly in my lectures. And in my workshops, I always bring a large stack of them—I hand them to the participants so they can see what I'm talking about when I discuss (my) photography. Every time, I notice how strong the reactions are. It also tells me something when someone can't get anything out of it.

Some photo books have opened windows for me, shown me new paths, or encouraged me to think differently. Others have simply confirmed my own ideas. I'm not a collector in the traditional sense, but I do have a large bookshelf here, full of books. And scattered throughout our apartment, they're stacked high. Some have reached considerable value. They range from works by world-famous photographers to small editions by artists known primarily regionally or nationally within amateur photography circles. From Lindbergh and Avedon to Purienne and Kate Bellm, to a self-published Polaroid collection by a photographer just around the corner. I collect because I simply enjoy looking at them.

That's why I want to write about books like this here on the blog. Not classic reviews – others can do that better. But rather impressions and thoughts that arise while leafing through them and that flow into my photographic work. Like with The Last Sitting by Bert Stern. Ready?

What it's about

The Last Sitting is no ordinary photo book. It gathers the last photographs of Marilyn Monroe – taken by Bert Stern in June 1962. A few days at the Bel-Air Hotel in Los Angeles, over 2,700 negatives, from which Vogue ultimately printed just twenty images. The first and only time during this icon's lifetime. The issue was published the week news of Marilyn's death spread around the world.

Bert Stern – from messenger boy to the “Original Mad Man” of photography

Stern was born in Brooklyn in 1929, the son of Jewish immigrants, and never had formal photographic training. He started as a messenger boy at Look magazine , later became an art director at an advertising agency, and taught himself photography.

During his time in the army in Japan in the early 1950s, he took his first photographs and learned about techniques such as lighting. His breakthrough came in 1953: the famous Smirnoff advertisement, featuring a bottle in front of the Pyramids of Giza. The slogan: "Smirnoff leaves you breathless." This wasn't just advertising; he created an image that, combined with the slogan, conveyed a mood in a new way. This was also remarkable because Russian vodka was a risk during the Cold War. The success was enormous, sales exploded, and Stern became overnight one of the most sought-after photographers of his generation—a true "Mad Man."

From the mid-1950s onward, he worked regularly for Vogue and Harper's Bazaar . His style was elegant, but never rigid. Perhaps because he was self-taught, a unique psychology flowed into his images. He thought in terms of movement and sought the still image within it. This gave his pictures a certain something.

He saw Marilyn Monroe for the first time in 1955 – at a party hosted by the Actors Studio . He was still a beginner, just one of many awestruck onlookers. "Like a moth to a flame," he later wrote. She was the goddess, he the novice. David and Goliath.

Marilyn Monroe – Myth

Marilyn Monroe – everyone knows the name, but many of today's younger generation only have a vague idea of who she really was. Born Norma Jeane Mortenson in Los Angeles in 1926, without a father and with a mentally ill mother, she grew up in foster homes and institutions.

She started working in a factory, was discovered by an army photographer, and soon became a model. In 1946, she signed her first film contract. Norma Jeane gradually became Marilyn Monroe – blonde, with a new voice, a new name. Two lives in one body.

In the 1950s, she became the biggest female star in the world. Films like Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and How to Marry a Millionaire made her a sex symbol. But the hype didn't come solely from Hollywood. It was the photographs of her that created a new image: sensual and vulnerable at the same time. Icon and girl next door in one.

This very contradiction was her core. Marilyn stood for youth, freedom, and glamour – but also for loneliness, doubt, and the dark side of fame. She was both projection and reality in one person. She experienced a level of fame (and in a way) that is hardly comparable to today's standards.

My personal relationship with Marilyn

She was never a sex symbol to me. I was young for that at a different time. For me, she—along with James Dean—was a symbol of youth and style. Of something mysterious, timeless. As a teenager, I found her films kitschy, light-years away from my reality. Only later did I understand what lay beneath the surface and learn more about her.

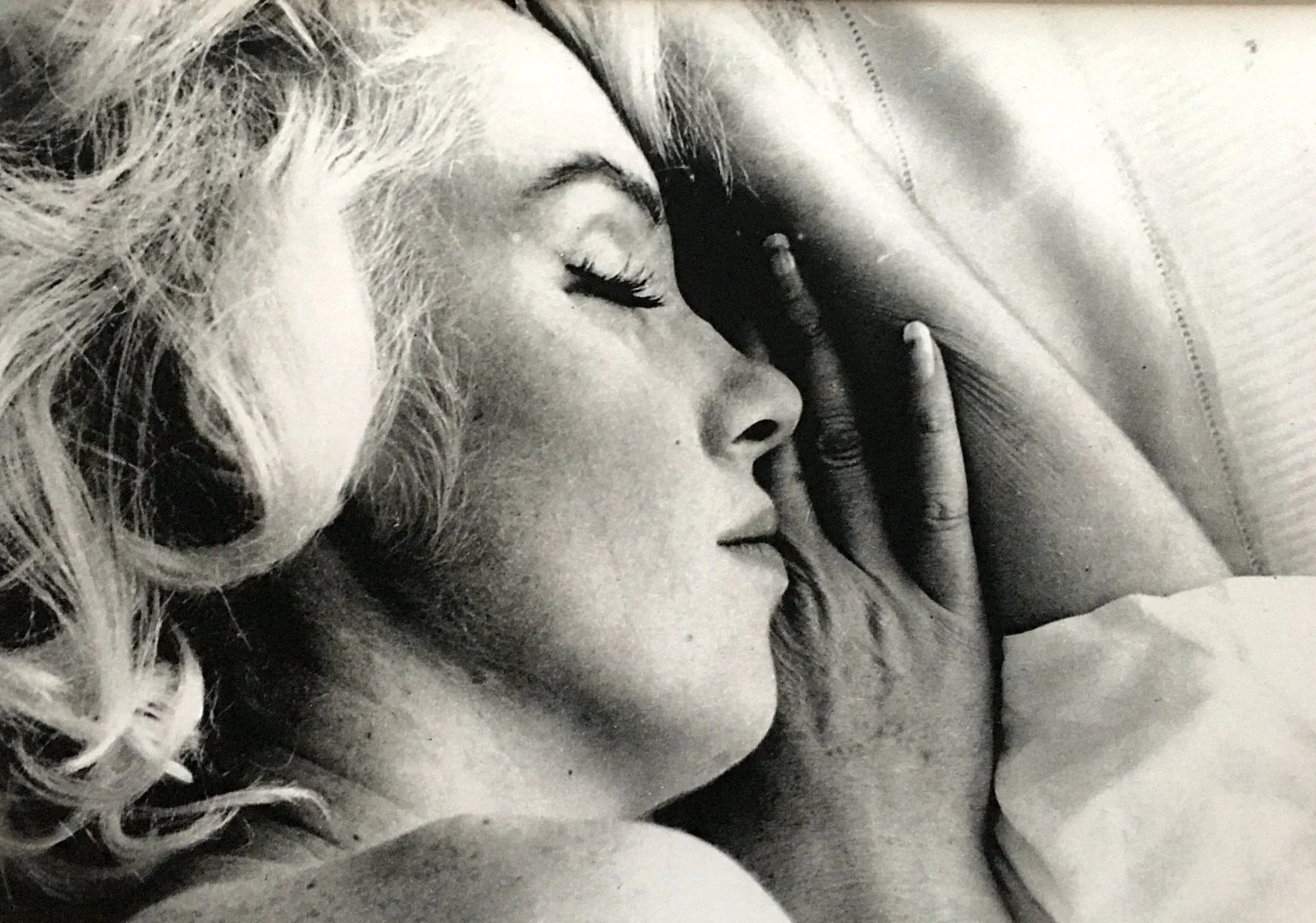

It was Eve Arnold's photographs of her that I particularly loved—because they show Marilyn as a person, not a myth. My first book, I think, was * Marilyn by Magnum* . And yet: In * The Last Sitting*, there are two images that, for me, rank among the greatest portraits ever taken. One shows her asleep, relaxed, almost defenseless (which perhaps doesn't even qualify as a portrait in the strictest sense). The other: in a black, backless dress, turned sideways into the light, her hair pulled back, yet she appears vulnerable at the same time. These two images are among my all-time favorites.

The setting of the story – the Bel Air Hotel

The photoshoot didn't take place in a studio, but at the Bel-Air Hotel. Opened in 1946, it quickly became a retreat for Hollywood stars like Grace Kelly, Elizabeth Taylor, and Judy Garland. A place of tranquility, hidden behind palm trees and gardens.

For Stern, it was perfect: neutral, discreet, yet steeped in history. Marilyn knew it well; she retreated there when her life was in turmoil—after failed marriages, during crises. The Bel-Air was renowned for its discretion and professionalism in dealing with celebrities.

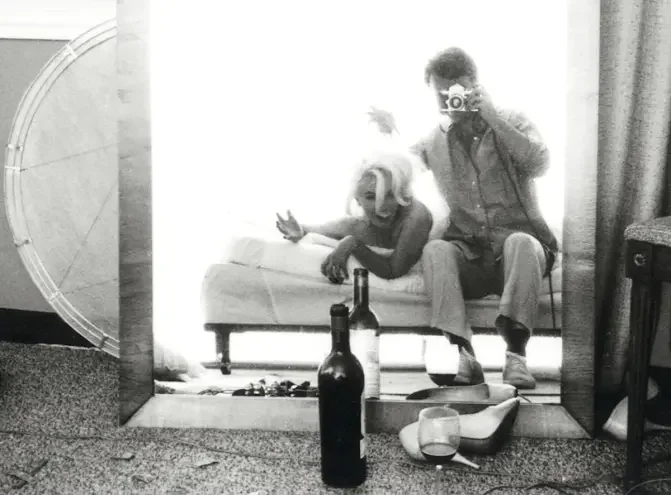

Self-portrait Monroe and Stern

It still exists today. In 2021, the Last Sitting photos were displayed there again for its 75th anniversary. Anyone sitting there today—at the bar or outside in the garden with its white bungalows and red roofs—might sense something of that past. An oasis in the heart of Los Angeles, designed in a Spanish-Mediterranean style.

Three and a Day – The Sittings

It all actually began a few weeks before the famous "Last Sitting." Stern finally mustered the courage to contact her for a shoot; he had previously been commissioned by Vogue to photograph her. Marilyn agreed and came to the first appointment alone. No stylists, no accompaniment. Just her, Stern, and the camera. The shoots sometimes went on late into the night and into the next morning. The setups were simple: paperbacks and flashes. Personally (and I think Stern himself would have preferred shooting in natural daylight). The two grew closer and soon found a rhythm in which Monroe agreed to undress. She rolled her pants down halfway and draped a cloth over her torso. That's how the first nude photograph came about—raw, casual, without any mystique.

Stern achieved his "goal for the day." He wanted her naked and without the second skin she usually wore for Hollywood glamour. In his writing, he describes how much he simultaneously adored and desired her. From today's perspective, some passages sound sexist. He was also newly married, with a wife and baby waiting for him at home. But it seems his real intention was to photograph her as Norma Jean. Difficult to reconstruct when both protagonists are no longer alive.

Stern submitted the photos to Vogue . It was the first time Marilyn had ever appeared there—one page. Maybe two. The photos were well-received. The editors felt that no one had ever photographed her so intimately and personally. But for Vogue, the fashion magazine, dresses and jewelry had to be included in the spread. Shortly afterward, Stern received a call and was commissioned to spend several more days at the Bel-Air Hotel. Eight pages were planned, a major spread. For Stern, it was a huge honor.

But this time everything was different: an entourage of stylists, makeup artists, and editors. A huge selection of dresses. And right in the middle of it all, Stern, who wanted something completely different: his picture. The one that would make her immortal. And you.

On the first day: Marilyn arrived, as always, hours later than agreed. Champagne, Polaroids, first attempts. She laughed, played, slipped away. Stern cautiously approached. Among other things, the black and white photos of her in the backless dress that I love so much were taken.

On the second day, the crew left the suite, and suddenly they were alone. Marilyn took off her dressing gown and lay down under a sheet. Intimacy returned. Stern photographed her—laughing, serious, vulnerable. The picture of her asleep, her head in the pillow, relaxed, unprotected, also dates from this period. Later, Stern wrote that they had also become physically intimate. He describes how things became so intense between them that he almost kissed her, which she rejected, only to then allow him to touch her and fall asleep. He writes that only the camera separated them. Whether that's true remains unclear. Perhaps this anecdote is also meant to underscore the drama of the scene. What remains is the image of the sleeping Marilyn.

Marilyn, asleep

She didn't come the next day. No call, no appointment. Stern waited. A break in the rules, as if she had rewritten them.

And finally, the grand finale on the last day. The picture he desperately wanted: Marilyn lying on the bed, photographed from above. No more playing, no more posing. Just clarity and connection between Bert Stern and Marilyn Monroe. In pictures he was to capture like a legacy. Stern had worked towards this for years.

This is how these days unfold: from the first spontaneous nude photo to the final portrait from above. In between, closeness, distance, omissions. Three days that reflect a whole spectrum of emotions.

After the shoot

For Stern, the shoot was over, but the real work was just beginning. Over 2,700 negatives lay before him, contact sheets full of Marilyn—laughing, serious, tired, naked, veiled. He spent days and nights reviewing, marking, and discarding them. Marilyn herself had crossed out some negatives with red nail polish or felt-tip markers, or pierced them with a hairpin, rendering them unusable, as if she wanted to make it clear once more who was in control, at least in retrospect. Remarkably, she allowed pictures showing the scar under her ribs from gallbladder surgery to pass, while destroying shots where her eyeliner wasn't perfect.

Then came the waiting. Stern recounted how he waited days and weeks for the call from the Vogue editors. Finally, the call came, along with the invitation to review the photos: a strictly limited selection. From the thousands of images, Vogue ultimately printed just twenty across eight pages. The editors opted for a stark black-and-white spread—elegant, serious, almost austere. No colorful experiments, no nude shots. It was a very deliberate selection: Marilyn as an icon, not as a girl, not as a sex symbol on demand.

The timing was fateful. As the issue went to print, news of her death arrived. August 1962. What was intended as a fashion history became an obituary. The images took on a gravity Stern had never planned. They became a kind of eulogy and Stern's most significant work.

After the climax

The Last Sitting was Stern's pinnacle. Afterwards, he continued to photograph – Elizabeth Taylor, Sophia Loren, Audrey Hepburn. But in the 1970s, his style no longer suited the new, harsher visual language. Added to this were alcohol, drugs, and failed marriages.

He himself said he could never shake Marilyn. Those three days in Bel-Air became a fixed point in his life. A triumph that became a burden for him. Only in the 1990s, with retrospectives and reissues, did recognition return. In his final years, he took up photography again – of stars like Kylie Minogue, Kate Moss, and Madonna.

Bert Stern died on June 26, 2013 in New York City, at the age of 83.

What I gained from this book

This book changed my perspective on the process of portrait photography. It showed me that patience is more important than technique. That you have to wait until someone lets their guard down. Norma Jeane and Marilyn Monroe—that was an extreme example. But it's precisely that moment I still seek today: when a person is no longer acting, but is truly present.

I recognize myself in much of what Stern describes: the path to eye level, the constant interplay of David and Goliath, the understanding of beauty as energy, not as the sum of individual features. The difference between the fact of beauty and the fantasy of it. Thinking in terms of movement, in films from which one extracts still images. And the layers that one uncovers layer by layer.

But I also have questions. How would she have aged, and how would she have developed in the 70s and 80s? How would I have photographed her? Would it even be possible to do a multi-day session with such a superstar today? In a time when everything moves so fast and so much has to be produced. What does "being naked" mean today?

Perhaps that is the true lesson of The Last Sitting : that a portrait is not a pose but a fragment – a snapshot of an experience with another person. Gone in the moment the shutter was released – and therefore unforgettable.

Marilyn in a black dress with a low-cut back