Fragments of Light No. 9: The Invisible Zone - Between Gaze and Self-Image

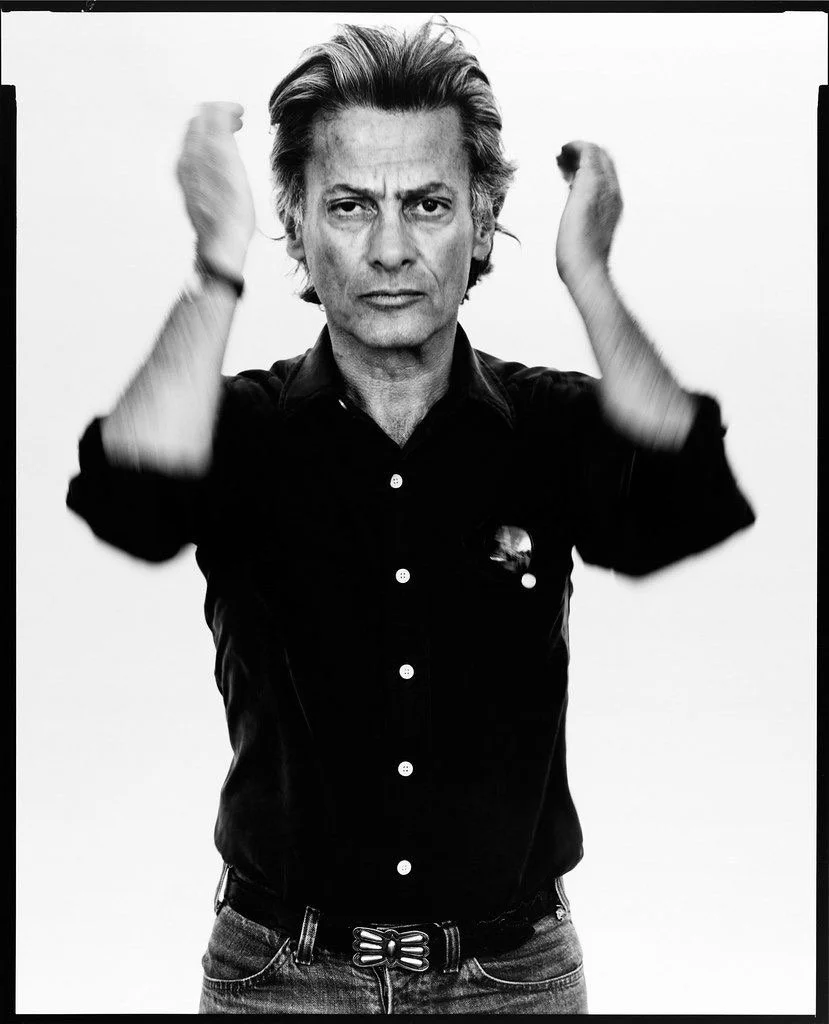

There's this self-portrait by Richard Avedon.

He's standing directly in front of the camera, like many of the people he's photographed. White background – his classic. Black shirt, his hair a bit too long, only roughly styled. The picture could have been taken just last year.

His arms are in motion. Probably unintentionally. The resulting blurriness makes the image even more intriguing. The eye is automatically drawn to his face. Sharp, focused, alert. As if he wanted to make something clear at that precise moment. Something like, that only he can do it exactly like that.

This photograph didn't primarily fascinate me because of its power. It preoccupied me because I asked myself: Why is he taking a self-portrait? What can he show with it that no one else could capture for him?

Richard Avedon

I'm also thinking of Annie Leibovitz, who photographed herself in the bathroom mirror of a San Francisco hotel room in 1970. Why?

Of Vivian Maier, who appears as a shadow, reflection, or fleeting silhouette in her own pictures. Why?

Of Claude Cahun, Francesca Woodman, Zanele Muholi. How they all portrayed themselves at some point. Why?

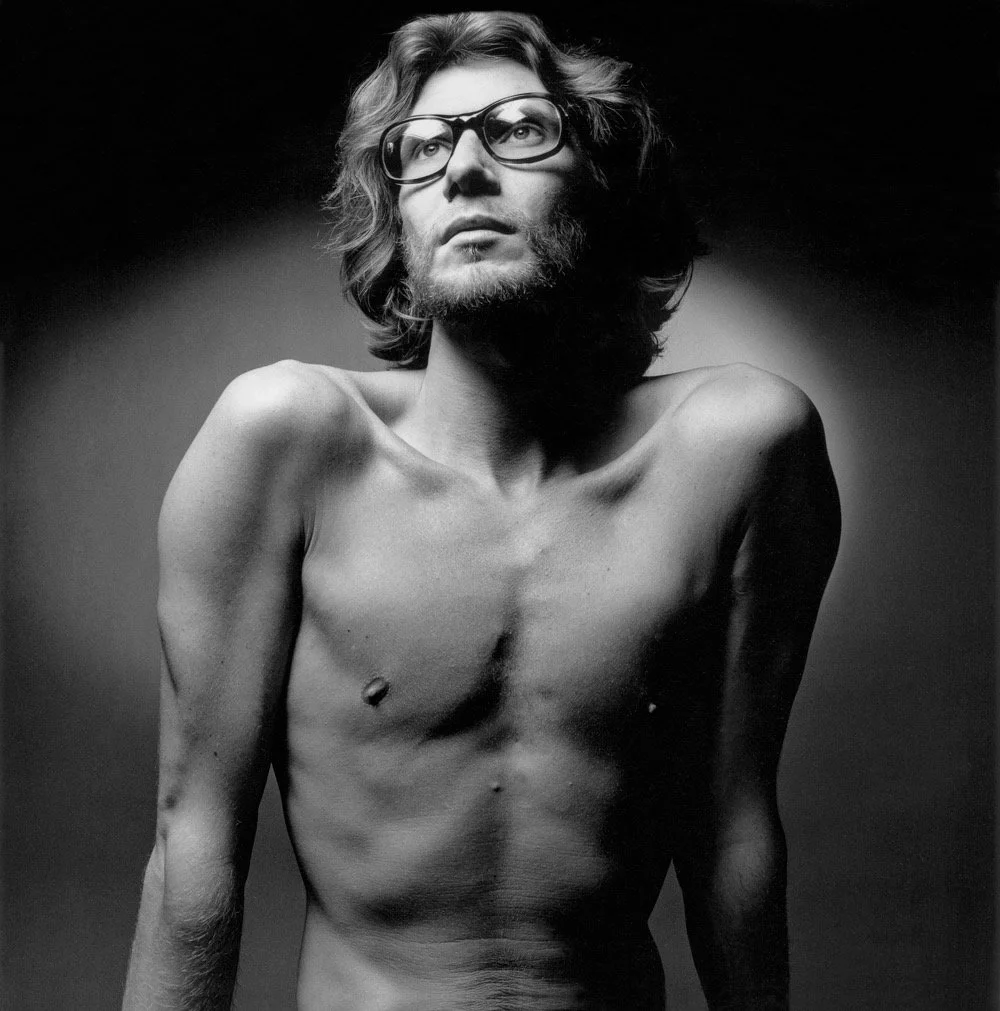

And then there's Yves Saint Laurent – photographed by Jeanloup Sieff. This famous nude photograph from a series.

For many years I actually thought it was a self-portrait.

It radiates such a controlled, deliberate gaze. As if he himself had decided how he wanted to be seen – and pressed the remote shutter release.

This has intrigued me so much: that a photograph, even if it's not of the person being photographed, can appear as a self-portrait.

Because in that brief moment, the photographer and the subject enter the same space – this neutral zone where their gazes meet and overlap on the person being photographed.

Yves Saint Laurent – photographed by Jeanloup Sieff

During a long car ride, an idea came to me, just like that – like a kind of discovery where scientists stumble upon something through serendipity.

I was thinking about self-portraits and suddenly realized: there's a zone where what I see of someone overlaps with what that person wants to show of themselves.

How large is this area?

And is it even a good thing if it's large?

There are self-portraits that say, "Let me do this. Only I can show myself as I am—or as I want to be seen."

Others hide. They turn their face away, let the camera in between, perhaps striking a pose they would never reveal with their face.

I'm not talking about selfies or snapshots here. I mean the world of photography, where a self-portrait is more than just a photo of oneself.

There's something magical about people portraying themselves.

And perhaps—because I find it so fascinating—this element unconsciously flows into my own photography. Perhaps that's precisely what makes a picture so intense: when something of this overlap is revealed in the moment of taking the photograph.

The zone between gaze and self-image

In portrait photography, there's a space where two perspectives intersect: the photographer's gaze and the subject's self-image. It's a neutral zone that appears unposed, yet doesn't arise by chance. It can't be forced. Rather, the working process is structured to allow it to emerge—by providing space for development, by being open, by permitting unplanned moments. Technique recedes into the background. The relationship and the connection are what truly matter.

The pressure to achieve a perfect surface is avoided. Skin retains its texture, shadows can be hard or soft, and the surroundings are allowed to leave traces on the image and contribute to it. Any smoothing that imposes too much order removes the image from this intersection where both perspectives meet.

The result is a portrait that belongs neither entirely to the photographer nor entirely to the person portrayed. It lies precisely in between – and perhaps it is this "in-between" that gives the image a special intensity.

Many photographers, inspired by great fashion and portrait photography, use black and white as a synonym for authenticity. However, this often creates a disconnect: Staged scenes, combined with digitally smoothed skin and brighter eyes, distance themselves from the direct encounter that constitutes true authenticity.

Self-portrait and trust

A self-portrait possesses a unique magic: it is a moment in which the person taking the portrait alone determines how they wish to reveal or conceal themselves. Everything – perspective, expression, timing – lies in their own hands.

And yet, there are portraits that, although taken by someone else, possess the same power as a self-portrait. The photographs of Yves Saint Laurent by Jeanloup Sieff are one example. At first glance, one might think Saint Laurent had staged himself. His presence in the image is so direct, so natural.

Such photographs arise when the person being portrayed grants the photographer something that is normally only possible in self-staging – and the photographer doesn't disrupt this trust but rather preserves it. In such moments, the two perspectives merge, and the image bears traces of both: the self-determination of the person portrayed and the openness of the photographer.

The connecting element

The unique impact of an image often arises in this invisible space in between. It is a space where control and letting go, closeness and distance, self-image and the view of others find a balance.

And perhaps it is precisely this fragile balance that decides whether an image merely depicts – or has a lasting impact – and is truly unique.

The unique impact of a portrait doesn't come from perfect lighting, the choice of lens, or certainly not from a "look" that can be applied to any image. It arises in that invisible space between photographer and subject—where two emotions touch without merging. (Sorry for so much meta-level thinking.)

In this space, every image possesses something unique, something irreplaceable. It's the antithesis of images that appear to have been shot through a camera—perfect, smooth, interchangeable. Images that any decent app can generate tomorrow because they lack what can only emerge from this encounter: a mark of trust, timing, and genuine presence in the moment.

Perhaps that's the secret ingredient. It makes the difference between a picture you look at – and a picture that looks at you.